When a life-saving drug runs out, who gets it? This isn’t science fiction. It’s happening right now in hospitals across the U.S. In 2023, there were 319 active drug shortages documented by the FDA - and many of them were critical cancer drugs like carboplatin and cisplatin. When these shortages hit, doctors don’t just wait. They make impossible choices. One patient gets the dose. Another doesn’t. And without clear rules, those decisions are often made in panic, not principle.

Why Rationing Happens - And Why It’s Necessary

Drug shortages aren’t new, but they’ve gotten worse. In 2005, there were 61 reported shortages. By 2011, that number jumped to 251. Today, it’s over 300. The main culprits? A handful of manufacturers control most of the generic injectable market - just three companies make 80% of these drugs. If one factory has a quality issue, production halts. No backups. No alternatives. And when that happens, hospitals run out fast. Oncology drugs are hit hardest. Between March and August 2023, 70% of U.S. cancer centers reported severe shortages of carboplatin and cisplatin. These aren’t optional meds. They’re the backbone of treatment for ovarian, lung, and testicular cancers. Without them, survival rates drop. So when supply can’t meet demand, someone has to decide who gets treated. That’s rationing. And it’s not about being cruel. It’s about being fair when there’s no other option.The Ethical Frameworks That Guide These Decisions

Good rationing isn’t random. It’s built on ethics. The most respected model comes from Daniel and Sabin - called “accountability for reasonableness.” It has four rules:- Publicity: Everyone must know how decisions are made.

- Relevance: Criteria must be based on medical evidence, not personal bias.

- Appeals: Patients or families can challenge a decision.

- Enforcement: There must be oversight to make sure rules are followed.

- Decisions should be made by a team - not one doctor at the bedside.

- The team must include pharmacists, nurses, ethicists, and patient advocates.

- Patient communication is mandatory. No one should be left in the dark.

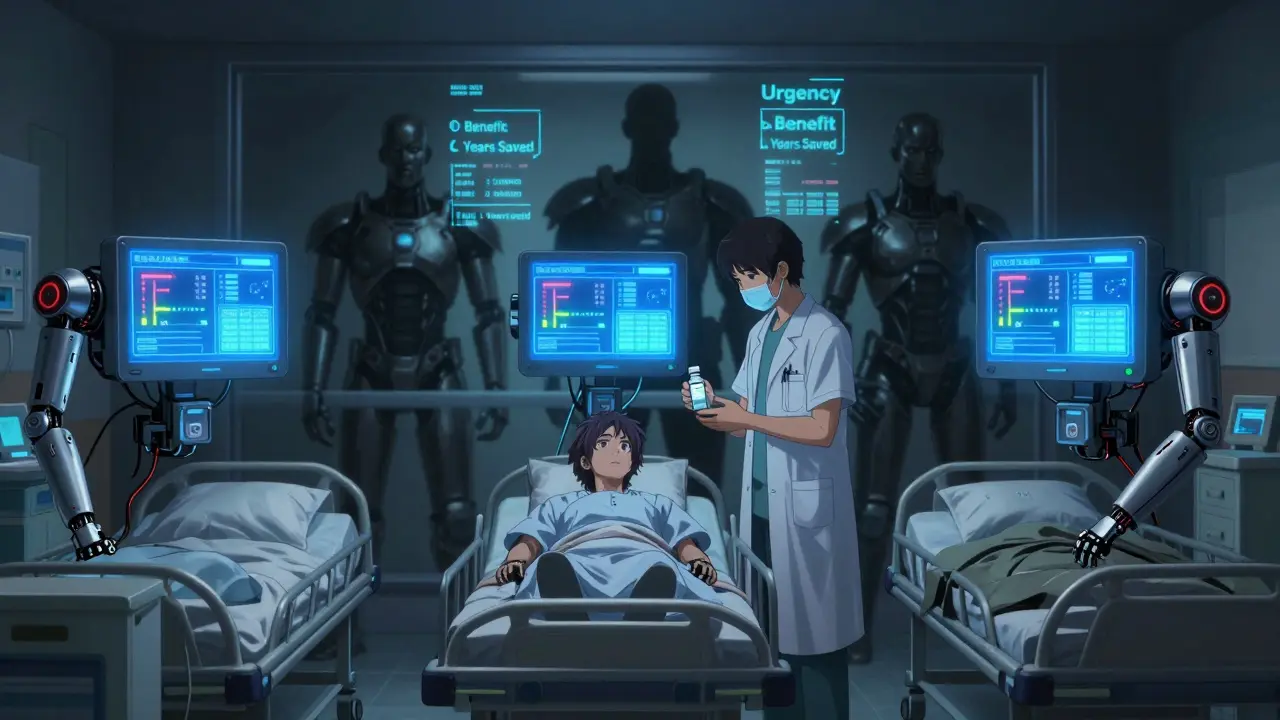

- Urgency: Who needs it now to survive?

- Likelihood of benefit: Who’s most likely to respond?

- Duration of benefit: Who will live longer with the treatment?

- Years of life saved: Prioritizing younger patients when outcomes are equal.

- Instrumental value: Should healthcare workers get priority to keep the system running?

What’s Actually Happening in Hospitals - The Gap Between Policy and Practice

Here’s the problem: most hospitals don’t follow these rules. A 2022 study in JAMA Internal Medicine found that 51.8% of rationing decisions were made by individual doctors or nurses - no committee, no transparency, no appeal process. That’s bedside rationing. And it’s dangerous. Clinicians who make these calls alone report 27% higher burnout rates. They’re traumatized. One oncologist told a forum: “I’ve had to choose between two stage IV ovarian cancer patients for limited carboplatin doses three times this month - with no institutional guidance.” Even worse, only 36% of patients are told they’re being rationed. That’s not just unethical - it’s a breach of trust. Families deserve to know why treatment was delayed or changed. The Patient Advocate Foundation recorded 127 formal complaints in 2021 about undisclosed rationing. And then there’s the “hoarding” problem. Departments sometimes stash drugs for their own patients, leaving others with nothing. A 2018 survey found 68% of pharmacists saw this happen. It’s human nature - protect your own. But it makes the shortage worse for everyone else.

Why Some Hospitals Get It Right

The hospitals that handle shortages well have one thing in common: they have standing ethics committees. These aren’t ad-hoc groups formed when a crisis hits. They’re permanent teams with clear roles:- 2 pharmacists

- 2 nurses

- 2 physicians

- 1 social worker

- 1 patient advocate

- 1 ethicist

- Tier 1: Curative intent, no alternative drug available.

- Tier 2: Palliative intent, but treatment significantly improves quality of life.

- Tier 3: Experimental or low-benefit use - deferred.

The Big Failures - And Who Gets Left Behind

The biggest flaw in current systems? They ignore equity. A 2021 report from the Hastings Center found that 78% of rationing protocols don’t include any metrics for racial, economic, or geographic fairness. That means patients in rural areas, low-income neighborhoods, or minority communities are more likely to be denied care - not because they’re less sick, but because their hospital doesn’t have the resources to build a fair system. Rural hospitals are hit hardest. 68% have no formal rationing protocol. Academic centers? Only 32% lack one. So if you live in a small town, your chance of getting life-saving treatment during a shortage is already stacked against you. And let’s not forget: these shortages aren’t random. They’re tied to how drugs are made. Most generic injectables are produced overseas. Supply chains are fragile. Regulations are weak. And manufacturers aren’t punished for failing to report shortages early. Only 68% meet the 6-month notification requirement.

What’s Being Done - And What’s Coming Next

Change is slow, but it’s coming. In May 2023, ASCO launched an online decision support tool to help hospitals apply ethical criteria in real time. In April 2023, Minnesota became the first state to publish binding allocation guidelines for two key drugs. The FDA’s new Drug Shortage Task Force is building an AI-powered early warning system - aiming to cut shortage duration by 30% by 2025. The National Academy of Medicine is working on standardized ethical metrics - draft rules expected in early 2024. And the American Society for Bioethics and Humanities is launching pilot certification programs for hospital rationing committees in 15 states as of January 2024. These aren’t just paperwork. They’re the first steps toward making rationing predictable, fair, and humane.What You Can Do - Even If You’re Not a Doctor

You don’t need to be in a hospital to care about this. If you or a loved one is on a drug that’s been on the FDA’s shortage list, ask your provider:- Is there a rationing protocol here?

- Who makes the decisions?

- How will I be informed if my treatment changes?

- Are alternatives available?

12 Comments

Henry Sy

So let me get this straight - we’re letting some guy in a white coat decide who lives based on a spreadsheet? That’s not ethics, that’s D&D character sheets with a side of moral panic. I’ve seen nurses cry after picking who gets the last vial. No one should have to play god like this.

says haze

The real failure isn’t the shortage - it’s the epistemic collapse of medical institutions that outsource moral reasoning to algorithmic heuristics while pretending they’re neutral. The Sabin framework is a beautiful abstraction, but when applied by underpaid, overworked clinicians with no institutional backing, it becomes performative ethics - a ritualistic appeasement of liberal guilt without structural accountability.

The fact that 51.8% of decisions are made solo reveals not a breakdown in protocol, but the systemic abandonment of ethical infrastructure. This isn’t rationing. It’s triage by trauma.

Alvin Bregman

man i just dont get why hospitals dont have like a team that sits down and figures this stuff out before it blows up

why wait till someone is dying to start talking about who gets what

its like building a fire escape after the building is on fire

Anna Hunger

Thank you for this comprehensive and deeply necessary examination. The ethical frameworks outlined here are not merely academic - they are lifelines. Hospitals that fail to implement structured, transparent, multidisciplinary rationing protocols are not just negligent; they are violating the fundamental covenant of medical ethics: first, do no harm - even when harm is inevitable, it must be administered with dignity and due process.

Jason Yan

It’s wild to think that in 2024, we still treat life-saving drugs like they’re concert tickets - first come, first served, or whoever yells the loudest gets it. But the real tragedy? We already know how to fix this. We’ve got the frameworks, the data, the models. What’s missing is the collective will to make it mandatory. Why is it acceptable for a rural hospital in Nebraska to have zero protocol while Johns Hopkins has a whole ethics committee on standby? It’s not a resource issue - it’s a moral one. We prioritize profit over people in so many systems, and this is just another symptom.

And don’t get me started on how the drug manufacturers get off scot-free. If your factory shuts down and you don’t report it for six months, you should be fined, not just ‘reminded.’ This isn’t a supply chain hiccup - it’s corporate negligence dressed up as inevitability.

shiv singh

you people are so soft. if you cant afford the drug you dont deserve it. why should i pay for your cancer treatment when i work 80 hours a week and still cant buy a house? the system is broken because you let weak people run it. let the rich buy their way out and let the rest die. thats how nature works. stop pretending medicine is a right.

Sarah -Jane Vincent

EVERYTHING about this is a lie. The FDA knows exactly who’s hoarding. The pharmaceutical companies are in cahoots with the government to keep prices high and supply low. They want you to think it’s a shortage - but it’s a controlled scarcity. Why? To make you panic. To make you beg. To make you pay more. The ‘ethics committee’? A PR stunt. The real decision-makers are in boardrooms in New Jersey and Switzerland. Wake up.

Robert Way

why do they make these rules so complicated like who even cares about tier 1 tier 2 i just want to know if my mom gets the drug or not

and why do they say ‘instrumental value’ like nurses are extra points in a video game

Sarah Triphahn

It’s obvious. The people who get treated are the ones who have the loudest family members. The quiet ones? The ones without advocates? They disappear. This isn’t about ethics - it’s about social capital. If you’re poor, Black, or elderly, you’re statistically more likely to be the one left out. The ‘fair’ system? It’s just a filter for privilege.

Vicky Zhang

I just want to say - to every nurse, pharmacist, and oncologist reading this - you are not alone. I’ve seen your hands shake after making those calls. I’ve heard your voices crack when you say, ‘I’m so sorry.’ You’re not failures. You’re heroes holding the line in a system that abandoned you. Please, please, please - don’t carry this alone. Find your team. Speak up. You deserve support too.

Allison Deming

The absence of equity metrics in rationing protocols is not merely an oversight - it is a moral abdication. To design a system that does not account for race, income, geography, or access to advocacy is to institutionalize disparate outcomes under the guise of clinical neutrality. Justice is not a variable to be optimized; it is a foundational principle. Until equity is codified into the algorithm, every tiered decision is a quiet endorsement of systemic injustice.

Susie Deer

US first. We make the drugs. We pay for the research. Why should India or China get to break our supply chain and then we have to beg for medicine? Fix our factories. Stop outsourcing. End the foreign dependency. No more excuses.