When someone with Parkinson’s disease starts seeing things that aren’t there-people in the room, shadows moving, or loved ones saying things they never said-it’s not just unsettling. It’s terrifying. And the go-to solution? Antipsychotics. But here’s the cruel twist: the very drugs meant to calm those hallucinations can make walking, talking, and moving even harder. In fact, for many Parkinson’s patients, taking an antipsychotic can turn a manageable condition into a rapidly declining one.

Why Antipsychotics Are a Double-Edged Sword

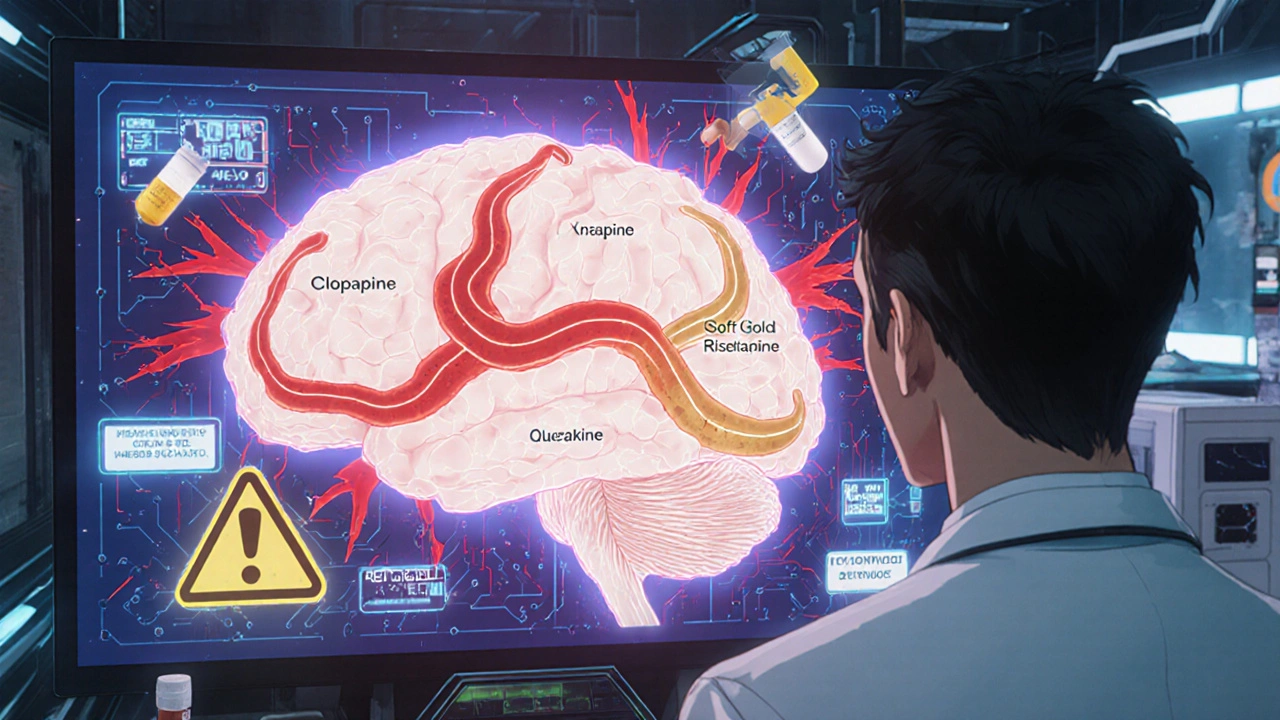

Parkinson’s disease is caused by the loss of dopamine-producing neurons in the brain. Dopamine isn’t just about feeling good-it’s essential for smooth, controlled movement. That’s why people with Parkinson’s struggle with tremors, stiffness, slow movements, and balance problems. These are the motor symptoms that define the disease. Now, psychosis in Parkinson’s-called Parkinson’s disease psychosis (PDP)-affects about 1 in 4 patients. Hallucinations and delusions often come later in the disease, sometimes after years of living with tremors and stiffness. When they appear, doctors are pressured to act. But most antipsychotics work by blocking dopamine receptors, especially the D2 receptor. That’s how they reduce hallucinations in schizophrenia. But in Parkinson’s, dopamine is already dangerously low. Blocking more of it doesn’t just help-it can crash motor function. It’s like trying to fix a leaky faucet by turning off the main water line. You stop the drip, but now the whole house runs dry.Which Antipsychotics Are Most Dangerous?

Not all antipsychotics are created equal. First-generation drugs-like haloperidol, fluphenazine, and chlorpromazine-are especially risky. Haloperidol, often used in hospitals for agitation, blocks 90-100% of D2 receptors at standard doses. In Parkinson’s patients, even tiny amounts-0.25 mg daily-can trigger sudden rigidity, freezing, or falls. Studies show 70-80% of Parkinson’s patients given haloperidol develop severe parkinsonism. The Parkinson’s Foundation advises avoiding these drugs entirely. Second-generation antipsychotics are often seen as safer, but many still carry major risks. Risperidone, for example, improves hallucinations in about half of patients-but at a cost. One 2005 study found that while risperidone reduced psychosis as well as clozapine, it made motor symptoms 4 times worse. Patients on risperidone had an average 7.2-point increase on the UPDRS-III motor scale. That’s the difference between being able to dress yourself and needing help for every button. Olanzapine isn’t much better. A 1999 study of 12 Parkinson’s patients showed 75% had worse movement after taking it. Only one stayed on the drug. And here’s the worst part: risperidone has been linked to a 2.5 times higher risk of death in Parkinson’s patients compared to those not taking antipsychotics.The Only Two That Don’t Make Things Worse

There are two antipsychotics that don’t wreck motor function-and they’re not even the most commonly prescribed. First is clozapine. It’s been FDA-approved for Parkinson’s psychosis since 2016. It blocks dopamine receptors weakly (only 40-60% occupancy) and also acts on serotonin receptors, which helps calm psychosis without crushing movement. In clinical trials, clozapine improved hallucinations in nearly half of patients with no meaningful increase in motor symptoms. But it’s not simple. Clozapine can cause agranulocytosis-a dangerous drop in white blood cells. That’s why patients need weekly blood tests for the first 6 months. If the count drops below 1,500 cells/μL, the drug must stop. Many doctors avoid it because of the monitoring burden. But for patients with severe psychosis and stable motor function, it’s often the only safe choice. The other is quetiapine. It’s used off-label because it doesn’t have FDA approval for Parkinson’s, but it’s the most common antipsychotic prescribed for PDP. It has even lower D2 receptor binding than clozapine. Many patients see improvement in hallucinations within days at doses of 25-100 mg daily. But here’s the catch: some high-quality studies, including a 2017 trial published in Neurology, found quetiapine performed no better than a sugar pill. That’s led to debate among experts. Still, many neurologists use it because it’s generally well-tolerated, doesn’t require blood tests, and rarely causes major motor worsening.

Before You Reach for an Antipsychotic

The best treatment for Parkinson’s psychosis? Sometimes, no antipsychotic at all. Many patients improve just by adjusting their Parkinson’s medications. Anticholinergics, dopamine agonists, and even levodopa can sometimes trigger hallucinations. Reducing or eliminating these drugs-especially if they’re taken at night-can clear up psychosis without any new meds. One 2018 study found that 62% of patients saw their hallucinations disappear after tweaking their Parkinson’s regimen. The key is to start with the least risky options first. Step one: review all medications. Step two: cut back on anticholinergics or dopamine agonists if possible. Step three: try lowering levodopa doses, especially in the evening. Only if those fail should you consider an antipsychotic.The New Hope: Pimavanserin and Lumateperone

In 2022, the FDA approved pimavanserin (Nuplazid), the first antipsychotic designed specifically for Parkinson’s psychosis that doesn’t block dopamine at all. Instead, it targets serotonin 5-HT2A receptors-the same pathway thought to drive hallucinations. In trials, it improved psychosis without worsening movement. That’s huge. But it’s not perfect. Post-marketing data showed a 1.7-fold increase in death risk, leading to a black box warning. Still, for patients who can’t tolerate clozapine or quetiapine, it’s an option. Even more promising is lumateperone. Currently in phase III trials, early results show it reduces hallucinations by 3.4 points on the psychosis scale with no measurable motor decline. Final results are expected in mid-2024. If confirmed, this could become the new standard-effective, safe, and without the blood monitoring of clozapine.

What Should You Do?

If you or a loved one has Parkinson’s and is experiencing psychosis:- Don’t accept antipsychotics as the first answer.

- Ask your neurologist to review every medication you’re taking-especially those for sleep, depression, or bladder control.

- Request a UPDRS motor score before and after any new drug is started.

- If an antipsychotic is needed, insist on clozapine or quetiapine. Avoid haloperidol, risperidone, and olanzapine at all costs.

- Know the signs of worsening: sudden freezing, increased falls, or inability to speak clearly. These aren’t just side effects-they’re red flags.

15 Comments

Olivia Gracelynn Starsmith

So many doctors just reach for haloperidol because it's fast and cheap but they don't think about the long term

My mom went from walking with a cane to being bedridden after one dose of risperidone

It wasn't psychosis that took her mobility it was the 'treatment'

Always ask for UPDRS scores before and after

And if they push an antipsychotic ask why not try adjusting levodopa first

kaushik dutta

Let me clarify this with clinical precision: the D2 receptor occupancy threshold for motor deterioration in Parkinsonian patients is approximately 70%

Haloperidol achieves 90-100% at therapeutic doses whereas clozapine hovers at 40-60%

Quetiapine's low affinity for D2 receptors explains its relative safety profile despite weak efficacy in controlled trials

Pharmacokinetic variability across ethnic populations further complicates dosing protocols especially in Indian subcontinental cohorts where CYP2D6 polymorphisms are prevalent

Skye Hamilton

they dont want you to know this but antipsychotics are just big pharma's way of keeping you dependent

the real cure is detoxing from sugar and gluten and doing yoga at sunrise

my cousin had hallucinations and she just started drinking lemon water and now she dances barefoot in the garden

theyll never tell you that

Hannah Magera

My grandma had Parkinson's and she saw people in the corner of the room for years

She never took any antipsychotics

We just turned off the TV at night and made sure her room had soft light

It stopped after a few weeks

Maybe it was just shadows and loneliness

Not every weird thing needs a pill

Austin Simko

the government controls the meds

they want you sick

clozapine is banned in 12 countries

they dont want you to walk

Maria Romina Aguilar

I find it deeply concerning that the medical community continues to normalize pharmacological interventions for what may be entirely non-pathological perceptual phenomena in elderly patients with neurodegenerative conditions...

And yet...

There is no consensus...

And the data is...

Contradictory...

And the FDA approval process...

Is compromised...

By...

Corporate interests...

And...

Well...

I just...

I think...

We need to...

Reconsider...

Everything...

Denise Wiley

I cried reading this

My dad was on haloperidol for three days and he couldn't hold his coffee cup anymore

He looked at me like I was a stranger

And then he whispered 'I'm sorry I can't move'

That's not psychosis

That's a crime

Thank you for writing this

Someone needs to scream this from the rooftops

Leah Doyle

This is so important!!

My aunt just started pimavanserin last month and her hallucinations are way better and she's dancing again 😭

She said she felt like she got her soul back

Doctors need to stop being scared of trying new things!!

Also anyone in the US ask about patient assistance programs for Nuplazid!! It's crazy expensive but there are ways!! 💛

doug schlenker

My neurologist pushed risperidone on my mom until I showed her this exact article

She switched to quetiapine and it was night and day

She still sees things sometimes but now she can feed herself and laugh again

It's not about erasing hallucinations

It's about keeping the person alive

Thanks for making this so clear

Aarti Ray

in india we dont even have access to clozapine or quetiapine for parkinsons

doctors just give olanzapine and say its fine

my uncle became rigid and stopped talking

now he needs full care

why dont they test drugs here before giving them to elderly

we are just lab rats

Nicola Mari

This is precisely why I refuse to trust modern medicine

They poison people under the guise of care

Psychosis is a spiritual awakening not a chemical imbalance

And now you're telling me they're using dopamine blockers on the elderly?

It's genocide wrapped in a white coat

And the FDA approves it?

Pathetic

Alexander Rolsen

Let’s be brutally honest: quetiapine is a placebo with side effects.

And clozapine? A nightmare with blood draws.

And pimavanserin? A money grab with a black box warning.

Meanwhile, the real solution-reducing anticholinergics-is ignored because it’s not profitable.

Big Pharma doesn’t sell ‘stop taking that pill’-they sell ‘take this new pill’.

And we’re all just pawns in their spreadsheet.

Brandon Trevino

Statistically speaking, the risk-benefit ratio for haloperidol in Parkinson’s psychosis is catastrophically negative with a number needed to harm of 1.3

Whereas the number needed to treat for clozapine is 2.7 with a relative risk reduction of 61% for hallucinations

Yet 80% of neurologists still prescribe risperidone due to inertia and lack of training in pharmacogenomics

This isn’t medical practice-it’s institutional malpractice

Michael Segbawu

USA is the only country that lets this happen

in europe they ban these drugs for elderly

why do we let corporations kill our grandparents

they dont care about your dad

they care about profit

shame on us

Katrina Sofiya

As a geriatric care coordinator with over 18 years in clinical practice, I cannot emphasize enough the importance of non-pharmacological interventions in Parkinson’s Disease Psychosis.

Environmental modifications-reducing visual clutter, ensuring adequate lighting, and establishing consistent routines-have been shown in multiple longitudinal studies to reduce hallucinatory episodes by up to 40% without pharmacological intervention.

Additionally, caregiver education and structured daily engagement significantly mitigate anxiety-driven perceptual distortions.

Before initiating any antipsychotic, a comprehensive medication review, including over-the-counter and herbal supplements, must be performed.

Anticholinergics, particularly diphenhydramine and oxybutynin, are frequent culprits.

Moreover, sleep hygiene must be addressed-nocturnal delirium is often misdiagnosed as psychosis.

And yes, while clozapine remains the gold standard for refractory cases, its use demands rigorous hematologic monitoring.

But the real tragedy is not the drug-it’s the systemic failure to prioritize patient autonomy, dignity, and holistic care over quick fixes.

We must shift from a disease-centered model to a person-centered one.

Patients are not their symptoms.

They are mothers, fathers, teachers, artists.

And they deserve to live-not just survive-with their humanity intact.

Thank you for this vital, compassionate, and meticulously researched piece.

It is exactly the kind of advocacy our field needs.