Multiple sclerosis isn’t just a neurological condition-it’s an immune system attack on the body’s own nervous system. Imagine your nerves as electrical wires, wrapped in a protective plastic coating called myelin. That coating helps signals travel fast and clear from your brain to your muscles, eyes, and organs. In multiple sclerosis (MS), your immune system, which is supposed to protect you from viruses and bacteria, turns against those myelin sheaths. It doesn’t just damage them-it strips them away, leaving nerves exposed and signals scrambling. The result? Vision blur, numbness, fatigue, walking trouble, and sometimes permanent disability.

What Happens Inside the Nervous System?

The attack starts when immune cells-mainly T cells and B cells-break through the blood-brain barrier, a natural shield that normally keeps harmful substances out of the brain and spinal cord. Once inside, these cells mistake myelin for a foreign invader. They release inflammatory chemicals, recruit more immune fighters, and begin tearing down the fatty insulation around nerve fibers. This process is called demyelination. What’s worse is that the damage doesn’t stop at the coating. Over time, the bare nerve fibers themselves-called axons-start to degenerate. Unlike skin or liver cells, nerve cells in the central nervous system don’t regenerate easily. Once an axon dies, the connection is gone for good. That’s why early treatment matters so much: it’s not just about stopping flare-ups, it’s about saving the wiring. Scientists have identified four distinct patterns of this damage in MS patients. Some show mostly T cells and macrophages chewing through myelin. Others show antibodies sticking to the damaged areas. One pattern even reveals that the myelin-producing cells, called oligodendrocytes, are dying off without being replaced. In all cases, the environment becomes toxic-like a war zone where repair crews can’t get in because the fighting never stops.Who Gets MS and Why?

About 2.8 million people worldwide live with MS. Women are two to three times more likely to be diagnosed than men, especially between the ages of 20 and 40. But it’s not just about gender. Geography plays a big role too. People living farther from the equator-like in Canada, Scandinavia, or northern U.S. states-have much higher rates. Why? Sunlight. Less sun means less vitamin D, and low vitamin D levels are linked to a 60% higher risk of developing MS. Another major trigger is the Epstein-Barr virus (EBV), the same virus that causes mononucleosis. A 2022 Harvard study found that people infected with EBV are 32 times more likely to develop MS than those who weren’t. It’s not that EBV causes MS directly-it’s that in genetically vulnerable people, the virus seems to confuse the immune system, making it start attacking myelin. Smoking also increases your risk by 80% and speeds up disability. Genetics matter too. If a parent or sibling has MS, your risk goes up-but even then, most people with a family history never develop it. It’s a mix: genes load the gun, environment pulls the trigger.

What Do the Symptoms Feel Like?

Symptoms vary wildly because MS can strike anywhere in the brain or spinal cord. One person might lose vision in one eye. Another might feel like their legs are made of concrete. Fatigue hits 80% of patients-not the kind you can fix with coffee. It’s a deep, bone-tired exhaustion that comes on suddenly, even after a good night’s sleep. Numbness or tingling in the arms, legs, or face is common. Some describe it like a limb falling asleep-but it doesn’t wake up. Walking becomes harder as muscles lose their signal. About 42% of people with MS report trouble with balance or coordination. Then there’s Lhermitte’s sign: a sudden electric shock that runs down your spine when you bend your neck. It’s caused by damaged nerves in the cervical spinal cord. Or optic neuritis-when the optic nerve gets inflamed, vision blurs or turns gray over 24 to 48 hours. For many, it’s the first warning sign. These symptoms don’t happen all the time. Most people start with relapsing-remitting MS (RRMS), where flare-ups come and go. During a relapse, immune cells flood the CNS, creating new lesions. Then, for weeks or months, things calm down. But each attack leaves behind some damage. Over time, the gaps between relapses shrink, and recovery gets harder.How Is It Treated Today?

There’s no cure yet-but there are tools to slow the damage. Disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) are the backbone of treatment. They don’t fix existing damage, but they stop the immune system from making new attacks. Ocrelizumab is one of the most powerful. It targets B cells, which make up a big part of the problem. In clinical trials, it cut relapses by 46% in RRMS and slowed disability progression by 24% in primary progressive MS. Natalizumab blocks immune cells from crossing the blood-brain barrier. It’s incredibly effective-reducing relapses by 68%-but carries a rare but serious risk: progressive multifocal leukoencephalopathy (PML), a brain infection that can be fatal. Doctors test patients for the JC virus before starting it. Newer drugs are being developed to go beyond suppression. One promising approach is remyelination-helping the body regrow myelin. Clemastine fumarate, originally an antihistamine, showed in a phase II trial that it improved nerve signal speed by 35% in MS patients. That’s not a cure, but it’s the first real sign that repair might be possible. Blood tests are also becoming more precise. Serum neurofilament light chain (sNfL) levels above 15 pg/mL indicate active nerve damage with 89% accuracy. This lets doctors see if a treatment is working before symptoms get worse.

What’s on the Horizon?

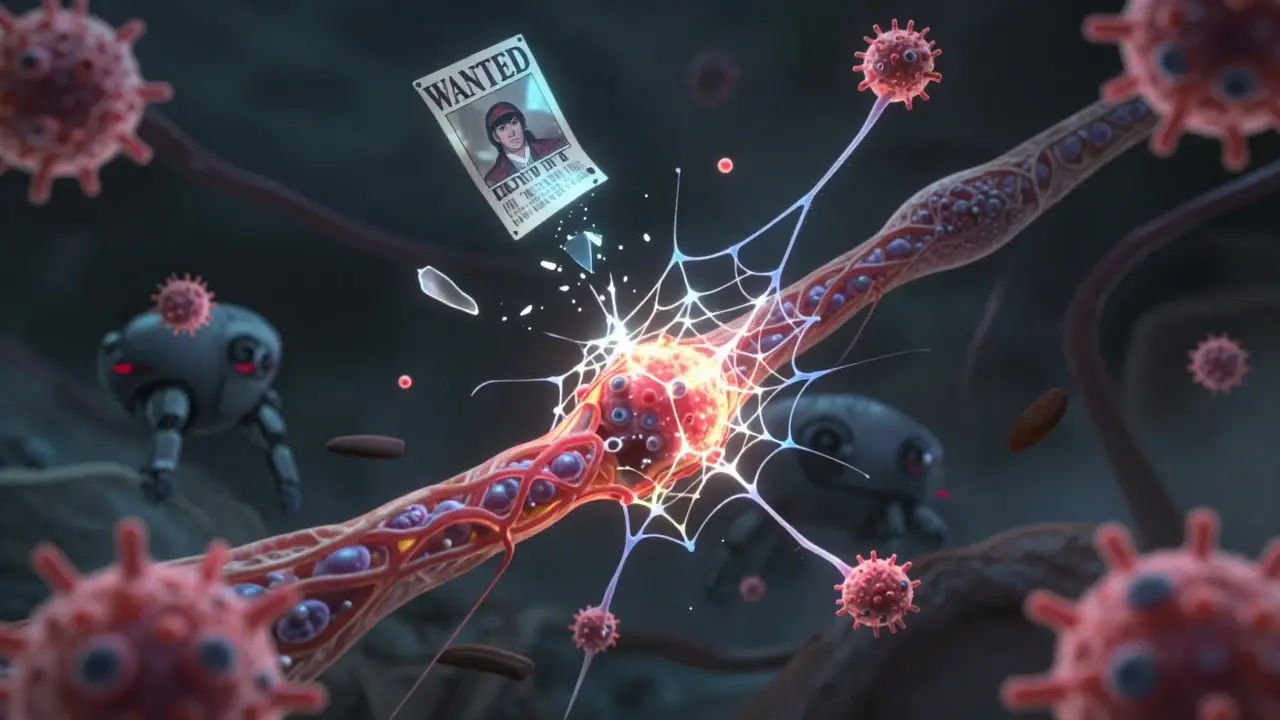

Researchers are now looking at the role of dendritic cells-immune sentinels that hang out near blood vessels in the brain. In MS patients, these cells are found holding up pieces of myelin like wanted posters, showing T cells exactly what to attack. Blocking these cells could stop the attack before it starts. Neutrophils, usually seen as short-term fighters, are also turning out to be troublemakers. They release sticky webs called NETs that tear apart the blood-brain barrier. In 78% of acute MS relapses, these NETs are present. New drugs targeting NETs are in early trials. The International Progressive MS Alliance has invested $65 million into research since 2014. Projects span 14 countries, focused on understanding why MS becomes progressive-when damage keeps growing even without flare-ups. That’s the hardest form to treat, and the one that leads to long-term disability.What Can You Do?

If you’ve been diagnosed, the most important thing is to start treatment early. Delaying increases the chance of permanent damage. Avoid smoking. Get regular sun exposure or take vitamin D supplements-especially if you live in a northern climate. Stay active. Exercise doesn’t cure MS, but it helps maintain strength, balance, and mental health. If you’re worried you might have MS-because of sudden vision loss, unexplained numbness, or extreme fatigue-see a neurologist. Early diagnosis means early intervention. MRIs can show lesions before symptoms even start in some cases. MS isn’t a death sentence. With modern treatments, many people live full, active lives. The immune system may have turned against the nervous system, but science is learning how to turn it back.Is multiple sclerosis hereditary?

MS isn’t directly inherited like eye color, but genetics do play a role. If a parent has MS, your risk goes up to about 2-5%, compared to 0.1% in the general population. Having a sibling with MS raises it to around 5%. Still, most people with a family history never develop it. It’s not one gene-it’s many, working together with environmental triggers like EBV and low vitamin D.

Can MS be cured?

There is no cure yet. But today’s treatments can stop or slow the immune system’s attack, prevent new lesions, and delay disability. Some people with relapsing-remitting MS go years without symptoms. Research into remyelination and neuroprotection is showing real promise, and clinical trials are testing drugs that could help repair damaged nerves.

Does MS always lead to wheelchair use?

No. Before modern treatments, about half of untreated MS patients needed walking aids within 15-20 years. Today, with early and consistent use of disease-modifying therapies, that number has dropped to around 30%. Many people with MS never need a wheelchair. Mobility depends on how early treatment starts, the type of MS, and lifestyle factors like exercise and avoiding smoking.

Can diet or supplements cure MS?

No diet or supplement can cure MS. But some, like vitamin D, omega-3s, and a balanced, anti-inflammatory diet, may help reduce flare-ups and support overall health. Vitamin D deficiency is strongly linked to higher MS risk and worse outcomes. Supplements can help if levels are low, but they’re not replacements for medical treatment. Always talk to your doctor before starting anything new.

Why do symptoms come and go?

In relapsing-remitting MS, symptoms flare up when immune cells attack the nervous system, causing new inflammation and lesions. During a relapse, nerve signals get disrupted. When the inflammation settles, the body may partially repair itself-myelin can regrow, and nerves can reroute signals. That’s why symptoms improve. But each flare leaves behind some damage. Over time, repair becomes harder, and symptoms may stick around longer or get worse.

Can stress cause MS flare-ups?

Stress doesn’t cause MS, but it can trigger flare-ups in people who already have it. Studies show that major life stressors-like losing a job or the death of a loved one-can increase the chance of a relapse in the following weeks. Managing stress through sleep, mindfulness, therapy, or exercise helps reduce that risk. It’s not about being ‘calm all the time’-it’s about having tools to handle pressure.

8 Comments

Jacob Hill

Wow, this is one of the clearest explanations of MS I’ve ever read-seriously, thank you. The myelin-as-plastic-coating analogy? Perfect. I’ve got a cousin with RRMS, and this helps me understand why she gets that sudden, crushing fatigue even after sleeping twelve hours. It’s not laziness-it’s her nerves screaming for help.

Also, the part about EBV being a 32x risk factor? Mind-blowing. I never connected mono to MS before. Now I’m wondering if my own childhood illness was more than just a bad week with a sore throat.

And vitamin D-yes! I live in Minnesota, and my doctor made me take 5,000 IU daily. I thought it was just for bones. Turns out, it might be keeping my immune system from going full traitor.

Malikah Rajap

You know what’s wild? This whole thing feels like the body’s version of a broken firewall-your immune system is supposed to be the antivirus, but somehow, it got hacked by a virus that made it think your own wiring was malware. And now we’re just patching the holes while the system keeps crashing.

Also, I’ve been reading about the dendritic cells acting like wanted posters for myelin? That’s terrifyingly poetic. Like the immune system has a criminal database… and it’s hunting its own cells. Who authorized this? Why is no one arresting the real culprit? (Spoiler: It’s probably Epstein-Barr, and he’s been chilling in our lymph nodes since 2003.)

Also, I’m going to start yelling at people who say ‘MS isn’t that bad’-because if you’ve ever felt your leg turn to concrete mid-step, you’d know it’s not a lifestyle choice. It’s a betrayal.

Tracy Howard

Let’s be honest-this is why Canada has the highest MS rates in the world. Too much snow. Too little sun. Too much maple syrup and not enough vitamin D. We’re basically a giant petri dish for autoimmune nonsense.

And don’t get me started on Americans thinking they can ‘fix’ MS with turmeric lattes and yoga. My cousin in Vancouver got diagnosed at 28. She’s on ocrelizumab. She’s not drinking chamomile tea and ‘manifesting’ her nerves back to health. She’s fighting a war. And if you’re not taking disease-modifying therapies seriously, you’re not just ignorant-you’re dangerous.

Also, EBV? Of course. We’ve all had mono. But in North America, we’re so obsessed with ‘natural remedies’ that we ignore the science. Wake up. This isn’t a wellness trend. It’s neurology.

Aman Kumar

From a neuroimmunological standpoint, the pathophysiology of MS is a quintessential example of molecular mimicry gone catastrophically awry-EBV’s EBNA1 antigen exhibits homology with myelin basic protein, thereby inducing cross-reactive T-cell activation via epitope spreading. The blood-brain barrier’s disruption is mediated not only by matrix metalloproteinases but also by neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs), which, as recently elucidated in Nature Immunology (2023), serve as scaffolds for autoantigen presentation.

Furthermore, the clinical heterogeneity is attributable to regional epigenetic modulation of oligodendrocyte precursor cell (OPC) differentiation under hypovitaminosis D conditions-particularly in latitudinal gradients exceeding 40°N. The efficacy of B-cell depletion therapies like ocrelizumab underscores the centrality of humoral autoimmunity in progressive phenotypes.

Yet, the persistence of pseudoscientific narratives regarding ‘cures’ via ketogenic diets or CBD oil remains a disturbing testament to the erosion of scientific literacy in Western societies.

Lewis Yeaple

The data presented here is largely accurate, though I would caution against overstating the causal link between Epstein-Barr virus and MS. While the 2022 Harvard study is compelling, correlation does not equal causation. The relative risk increase of 32-fold is significant, but the absolute risk remains low-approximately 0.5% in EBV-positive individuals versus 0.015% in EBV-negative. This must be contextualized within population-level epidemiology.

Additionally, while vitamin D deficiency is associated with increased MS incidence, randomized controlled trials of supplementation have not demonstrated conclusive disease-modifying effects. The role of genetics is also more complex than the phrase 'genes load the gun' implies-over 230 loci have been implicated, many involved in immune regulation, not neurodegeneration.

Finally, the term 'repair crews can't get in' is metaphorical. Oligodendrocyte precursor cells do attempt remyelination, but the inflammatory milieu inhibits differentiation. This is why future therapies must target both suppression and regeneration simultaneously.

Jackson Doughart

I read this whole thing slowly. Twice.

I’ve known someone with MS for over a decade. I never understood what was really happening inside her body-just that some days she couldn’t walk, and other days she seemed fine. This broke it down without sugarcoating, but without crushing hope either.

The part about axons not regenerating? That hit me. It’s not just ‘bad days.’ It’s permanent loss. That’s why every dose of DMT matters. Not for the ‘cure’-but for the quiet, invisible act of preserving someone’s ability to hug their kid, or hold a coffee cup without shaking.

Thank you for writing this. Not everyone gets to see the science behind the struggle. And maybe that’s the real medicine here.

Jake Rudin

It’s funny, isn’t it? We’ve spent centuries trying to conquer nature-viruses, bacteria, cancer-and now we’re learning that the real enemy isn’t out there… it’s us. Our own immune system, designed to protect, turned assassin. The body doesn’t hate itself-it’s just confused. Like a dog chasing its tail, but the tail is your spinal cord.

And the worst part? The system is trying to fix itself. Oligodendrocytes are trying. Myelin is trying. The brain is rerouting signals like a city building detours after a bridge collapses.

So maybe the real question isn’t ‘how do we stop the attack?’

It’s: ‘How do we help the body remember what it’s supposed to protect?’

Lydia H.

My sister was diagnosed last year. She’s 31. She cried when she saw the lesions on her MRI. I didn’t cry-I just held her. This post? It’s the first thing I showed her that didn’t sound like a textbook or a sales pitch. It just… made sense.

Also, I just started taking vitamin D. Not because I think it’ll cure her. But because I want her to know I’m trying to understand. Even if it’s just one supplement, one conversation, one less ‘but you look fine’ comment.

Thank you for writing this. I’m sharing it with everyone.