Meglitinide Meal Timing Safety Checker

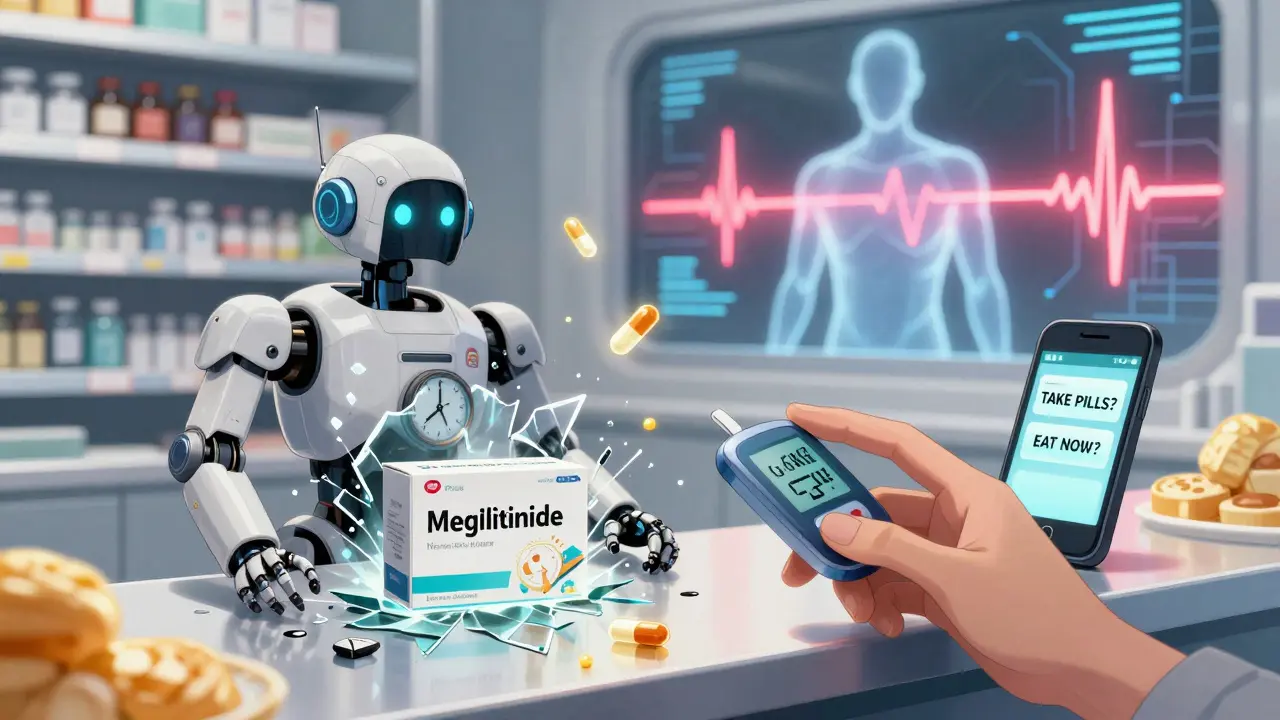

This tool helps determine if your meal schedule is safe when taking meglitinide diabetes medications (repaglinide or nateglinide). Remember: these drugs require precise meal timing to avoid dangerous hypoglycemia.

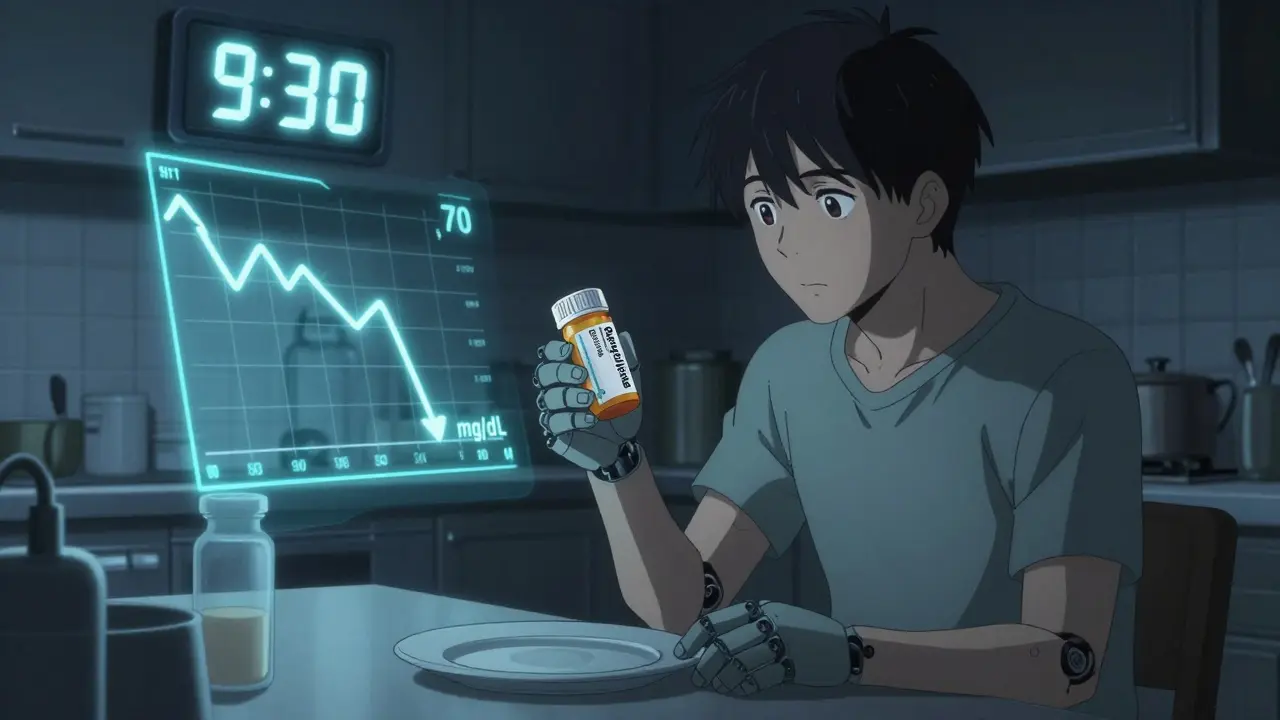

Take a diabetes medication like repaglinide or nateglinide, skip your lunch, and within 90 minutes your blood sugar could crash below 70 mg/dL. This isn’t a hypothetical risk-it’s a well-documented, life-threatening pattern tied directly to how these drugs work. Meglitinides were designed to help people with type 2 diabetes who don’t eat at regular times. But here’s the catch: they only work safely if you eat when you’re supposed to. Skip a meal, and you’re playing Russian roulette with your blood sugar.

How Meglitinides Work-And Why Timing Matters

Meglitinides, including repaglinide and nateglinide, are fast-acting insulin secretagogues. That means they tell your pancreas to release insulin quickly-within 15 to 30 minutes of taking them. Their effect peaks in about an hour and fades within 2 to 4 hours. That’s why they’re prescribed for people with unpredictable schedules: a night shift worker, someone with dementia who forgets meals, or a person whose appetite changes daily.

But this speed is also their weakness. Unlike sulfonylureas, which keep pumping out insulin all day, meglitinides are like a sprinter: they go hard, then stop. If you don’t eat right after taking them, there’s no food to absorb the insulin surge. Your blood sugar drops fast. Studies show skipping just one meal after taking a meglitinide increases hypoglycemia risk by 3.7 times. For older adults or those with kidney disease, the risk is even higher.

The Real Danger: Skipping Meals

It’s not just about forgetting breakfast. It’s about the timing mismatch. You take your pill at 8 a.m., thinking you’ll eat soon. But then your grandchild shows up, you get distracted, and lunch isn’t ready until 11 a.m. By 9:30 a.m., the drug is at peak action. Your insulin levels are high. Your blood sugar is falling. And you haven’t eaten a bite.

According to clinical data, 41% of hypoglycemia events in meglitinide users happen between 2 and 4 hours after dosing-the exact window when the drug is strongest and meals are most likely to be delayed. This isn’t random. It’s predictable. And it’s avoidable.

Research from Wu et al. (2017) found that patients who skipped meals while on meglitinides were far more likely to need emergency care for low blood sugar. The same study showed that people with advanced chronic kidney disease (eGFR under 30) had a 2.4-fold higher risk of severe hypoglycemia. Why? Because even though repaglinide is mostly cleared by the liver (making it safer than sulfonylureas in kidney patients), the body’s ability to respond to low sugar is still impaired.

Comparing Meglitinides to Other Diabetes Drugs

Let’s put meglitinides in context. Metformin doesn’t cause hypoglycemia on its own. SGLT2 inhibitors and GLP-1 agonists rarely do. Sulfonylureas like glipizide? They cause low blood sugar too-but because they work all day, even if you skip meals. Meglitinides are different. Their danger is tied to meal timing. If you eat regularly, they’re safer than sulfonylureas. If your meals are erratic, they’re riskier than almost anything else.

A 2004 study comparing repaglinide and nateglinide found repaglinide lowered HbA1c better (7.3% vs. 7.9%), but also caused 28% more hypoglycemia. Why? Because it’s slightly stronger and faster. Nateglinide is gentler, but still dangerous if meals are skipped.

Combining meglitinides with insulin or sulfonylureas? That’s a recipe for trouble. The insulin effects add up. The American Diabetes Association’s 2025 guidelines specifically warn against this combo unless absolutely necessary-and only with strict meal plans.

Who Should Use Meglitinides? Who Should Avoid Them?

Meglitinides aren’t first-line drugs. Metformin is. But they fill a real gap: people who can’t stick to a fixed eating schedule. Think:

- People with irregular work hours (nurses, truck drivers, shift workers)

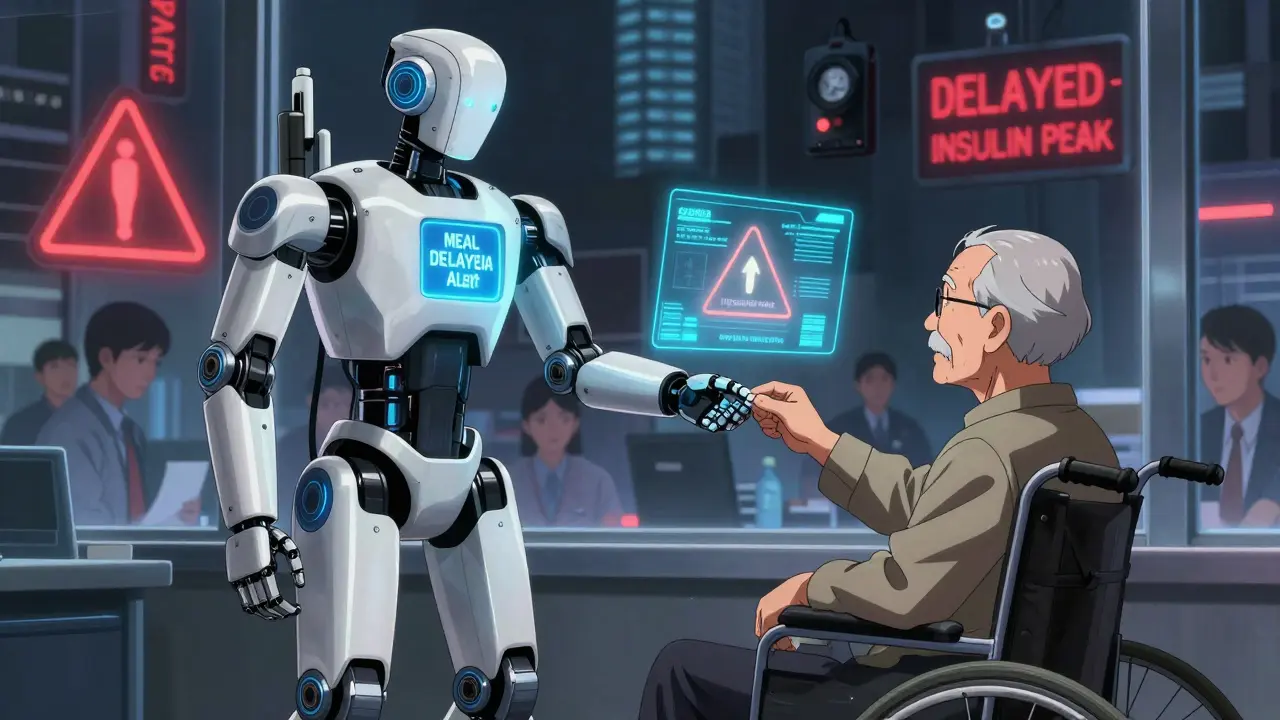

- Older adults with cognitive decline who forget meals

- Patients with kidney disease who can’t take sulfonylureas

- Those who had bad reactions to sulfonylureas

But they’re a bad fit for:

- People who frequently skip meals without warning

- Those with poor memory or no support system

- Anyone without access to glucose monitoring

And here’s the hard truth: if you’re living alone, forgetful, or don’t have someone to check on you, meglitinides might not be safe-even if they’re the best drug on paper.

How to Use Meglitinides Safely

If you’re on one of these drugs, here’s what you need to do:

- Dose only when you’re about to eat. Don’t take it at a fixed time. Take it 15 minutes before you sit down to eat. If you’re not eating, don’t take it.

- Never skip meals. Even a small snack-like a banana, a handful of nuts, or a slice of toast-can prevent a crash.

- Carry fast-acting sugar. Glucose tablets, juice, or candy should always be with you. If you feel shaky, sweaty, or confused, act fast.

- Use a CGM if you can. Continuous glucose monitors show real-time trends. Studies show they cut hypoglycemia episodes by 57% in meglitinide users with irregular eating.

- Use phone reminders. A 2023 trial found that simple smartphone alerts before meals reduced hypoglycemia by 39%. Set two: one for the pill, one for the meal.

Some doctors now use a "dose-to-eat" strategy: you only take the pill if you’re going to eat within 15 minutes. That’s the safest way to use these drugs.

The Future: Can We Fix This?

Researchers are working on solutions. A new extended-release version of repaglinide (repaglinide XR) is in Phase II trials. Early results show it reduces hypoglycemia by 28% in people with unpredictable meals. It’s not a cure, but it’s progress.

Meanwhile, apps that remind you to eat, smart insulin pens that track doses, and AI tools that predict meal times are being tested. But none of this replaces the core rule: no meal, no pill.

The FDA added strong warnings to meglitinide labels in 2021. The message is clear: these drugs are powerful tools-but only if you treat them like precision instruments, not casual pills.

Bottom Line

Meglitinides are not for everyone. They’re not for people who want a set-it-and-forget-it diabetes solution. They’re for people who need flexibility-and who are willing to be disciplined about eating. If your meals are unpredictable, and you’re not careful, these drugs can put you in the hospital. But if you eat when you take them, they can help you control your blood sugar without the all-day insulin pressure of sulfonylureas.

The choice isn’t just about which drug to take. It’s about whether your lifestyle can match the drug’s demands. And that’s something no pill can fix for you.

13 Comments

Donny Airlangga

This is such an important post. I work in geriatrics, and I've seen too many elderly patients crash after skipping meals because they forgot to eat. The timing thing with meglitinides? It's brutal. One guy thought he'd wait for his daughter to come home-he didn't realize the drug was already peaking. He ended up in the ER with a seizure. No one should have to live like that.

Evan Smith

So let me get this straight-you’re telling me I can’t just pop a pill and forget about it? Like, I gotta be a robot with a lunch schedule? Cool. I’ll just switch to metformin and call it a day. Why does diabetes care so much about my lunch breaks?

Manish Kumar

It’s not just about the drug, man-it’s about the illusion of autonomy in modern medicine. We’re told we can manage our own health, but the system demands perfect compliance. You take a pill for a disease that’s shaped by poverty, stress, and broken routines-and then you’re blamed when you miss a meal? That’s not healthcare. That’s performance art with a stethoscope. The real question isn’t ‘why do meglitinides cause hypoglycemia?’ It’s ‘why do we expect people to be flawless in a broken world?’

christy lianto

I’m a nurse and I’ve seen this happen. One woman took her pill because she thought she’d eat soon-then her car broke down. She sat in the parking lot for two hours. By the time she got to the clinic, she was trembling, sweating, and couldn’t speak. We gave her juice and glucose gel. She cried and said, ‘I didn’t mean to be bad.’ You can’t punish someone for being human. These drugs need better safety nets.

Annette Robinson

If you’re on a meglitinide, I really hope you have someone who checks in on you. Or a phone alarm. Or a banana in your purse. This isn’t just medical advice-it’s survival. And if you’re caring for someone who is, please don’t underestimate how easy it is to miss a meal. It’s not laziness. It’s distraction. It’s fatigue. It’s life.

Dave Old-Wolf

Wait, so if I skip lunch, I’m basically playing Russian roulette? That’s wild. I thought diabetes was just ‘eat less sugar.’ Turns out it’s more like ‘don’t forget to eat, or you’ll pass out.’

Molly Silvernale

It’s like… the body’s a symphony, right? And insulin is the conductor. Meglitinides? They’re the solo violinist who shows up early, plays loud, then vanishes. If the rest of the orchestra doesn’t come in with the food? Silence. Chaos. A crash. And no one’s there to say, ‘Hey, we forgot the melody.’ We treat diabetes like it’s a math problem. But it’s poetry. And poetry needs rhythm. Not just pills.

Ken Porter

Americans think medication is magic. It’s not. It’s a tool. And tools need instruction manuals. If you can’t follow basic meal timing, maybe you shouldn’t be on this drug. Stop blaming the medicine. Fix your life.

swati Thounaojam

my grandma took this and forgot to eat… she got real sick. now she only takes it when she sees food. smart.

Luke Crump

So… you’re saying the real problem isn’t diabetes? It’s capitalism? That we’re all too tired, overworked, and disconnected to eat on time? And now we’re being told to take a pill that only works if we’re perfectly scheduled? That’s not medicine. That’s a corporate scam dressed in white coats. I’m not taking it. I’m taking a nap.

Aubrey Mallory

I’ve worked with folks who are homeless or in shelters-no one’s reminding them to eat. These drugs? They’re dangerous without support systems. We need community health workers checking in, not just prescriptions. And if you’re a doctor prescribing this to someone without a fridge? You’re failing them.

Kristina Felixita

my cousin from india uses this drug and she always carries jaggery candy in her purse… like, literally always. she says it’s her ‘emergency sweet.’ i think that’s the most beautiful thing. she turned survival into ritual. love that.

Prakash Sharma

Finally someone says it. In India, we don’t have CGMs or phone reminders. We have grandmas who yell from the kitchen, ‘Beta, eat!’ That’s the real tech. No app can replace a mother’s voice saying, ‘Don’t skip lunch.’ This drug? It needs culture, not just code.