Drug shortages aren’t just inconvenient-they’re life-threatening. In the third quarter of 2025, 98% of U.S. hospitals reported at least one critical drug shortage. Insulin, chemotherapy agents, antibiotics, and even basic IV fluids vanished from shelves, forcing doctors to make impossible choices: delay treatment, substitute less effective drugs, or risk patient safety. And while patients and providers scramble, Congress has quietly introduced two bills meant to fix this. But are they enough?

The Two Bills at the Heart of the Crisis

The most direct response so far is the Drug Shortage Prevention Act of 2025 (S.2665). Introduced by Senator Amy Klobuchar in August 2025, this bill asks one simple thing: manufacturers must tell the FDA when demand for a critical drug starts to spike. Right now, companies aren’t required to report rising demand until it’s too late-often after a shortage has already begun. This law would force them to notify the agency at the first sign of trouble, giving regulators time to step in, find alternative suppliers, or even ramp up production.

It sounds straightforward, but here’s the catch: the bill doesn’t define what counts as a "critical drug." Does it include common antibiotics? Painkillers? Blood pressure meds? Without clear definitions, enforcement becomes a guessing game. There’s also no mention of penalties for non-compliance, no timeline for implementation, and no funding allocated to help the FDA handle the new workload. The agency already has a backlog of unreviewed shortage reports. Adding more paperwork without more staff or tools won’t fix anything.

Then there’s H.R.1160, the Health Care Provider Shortage Minimization Act of 2025. Unlike S.2665, this bill has almost no public details. No summary. No sponsor list. No committee assignment. All we know is the title. But based on what’s happening on the ground, we can guess what it’s trying to do. Over 122 million Americans live in areas where there aren’t enough primary care doctors. Hospitals are turning away patients because they can’t hire nurses or pharmacists. This bill likely targets workforce gaps-maybe by expanding loan forgiveness for medical students, speeding up visa approvals for foreign-trained providers, or increasing funding for training programs. But without the full text, no one can say for sure.

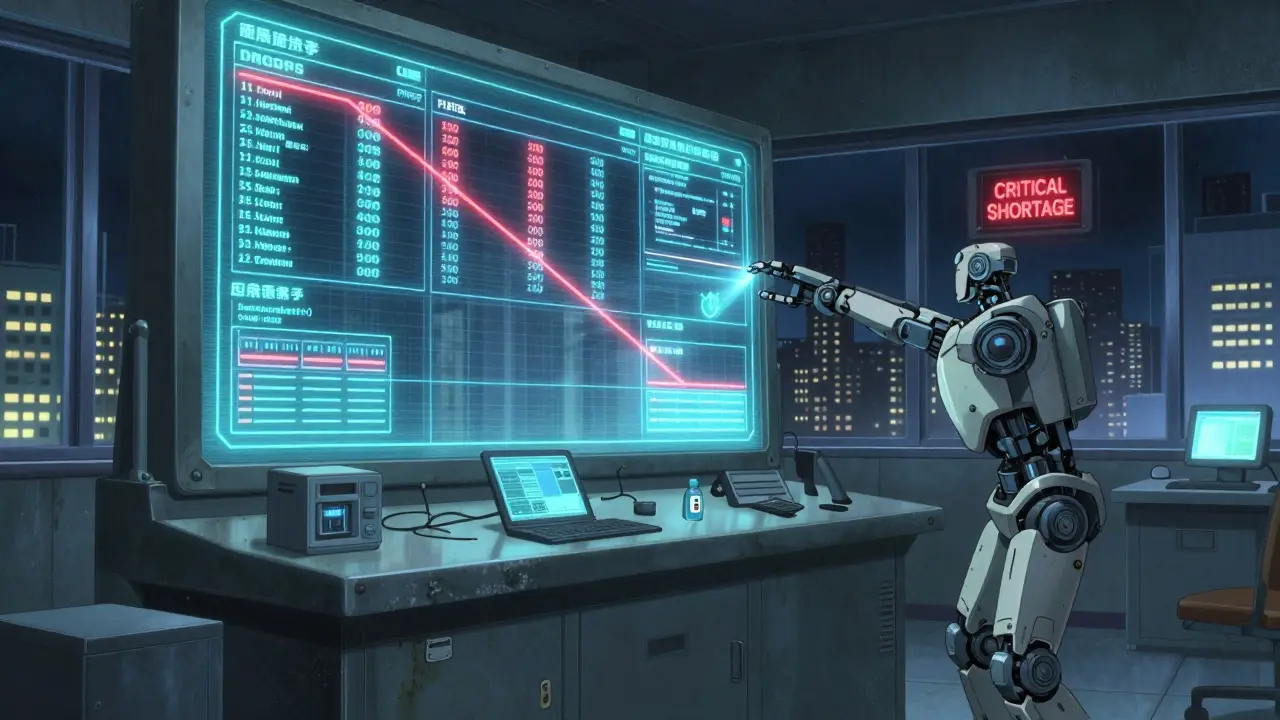

The Shutdown That Stopped Everything

Here’s the real problem: neither bill is moving. Not because they’re unpopular. Not because they’re flawed. But because the U.S. government shut down on October 1, 2025-and it’s still shut down as of February 2026. This is the longest shutdown in U.S. history, now in its 135th day. Over 800,000 federal workers are furloughed. The FDA? Partially closed. The CDC? Operating on skeleton staff. The Department of Health and Human Services? Mostly offline.

That means the FDA can’t review new shortage reports. It can’t update its public Drug Shortage Portal. It can’t even answer calls from hospitals asking where to find a replacement for a missing drug. The portal, which used to be a lifeline for pharmacies and clinics, now shows outdated data. Some hospitals report the site displays drugs as "available" when they’ve been out of stock for weeks.

And while Congress debates whether to fund border security or foreign aid, the people who need insulin or cancer drugs are left in the dark. The Congressional Budget Office estimates the shutdown costs the economy $1.5 billion every single day. That’s more than enough to fund the $45 million a year S.2665 would need to make its notification system work. But money for health isn’t on the table. Instead, lawmakers are fighting over $7.9 billion in foreign aid cuts and $1.1 billion in public media cuts.

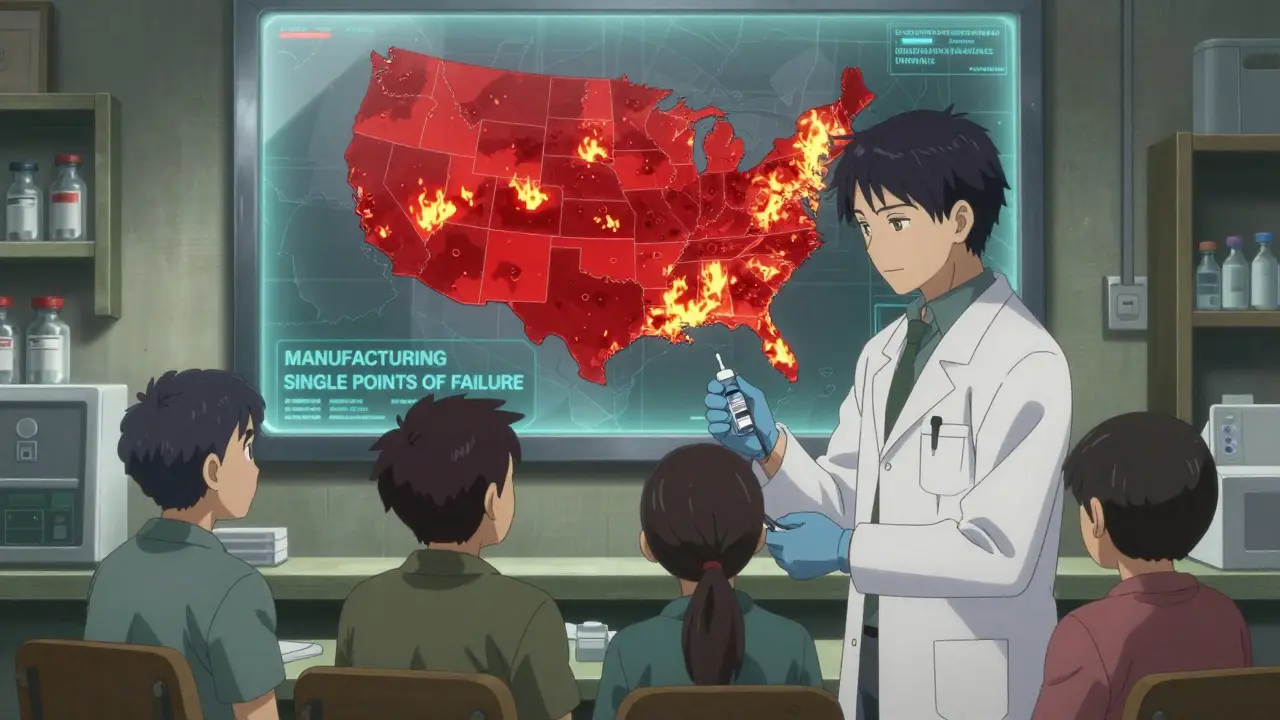

Why This Isn’t Just a Government Problem

The root of drug shortages isn’t Congress. It’s the system. Sixty-three percent of shortages come from manufacturing delays-often because a single factory overseas makes 80% of a drug’s active ingredient. If that factory has a power outage, a quality control issue, or a labor strike, the whole country goes without. The FDA knows this. But it doesn’t have the authority to force companies to diversify their supply chains.

And it’s not just drugs. The U.S. is facing a collapse in healthcare staffing. The American Association of Medical Colleges predicts a shortfall of 124,000 physicians by 2034. Nurses are quitting in droves. Pharmacists are working 12-hour shifts with no breaks. H.R.1160 might help-if we ever find out what’s in it. But right now, it’s a ghost bill. No one’s talking about it. No one’s even sure who introduced it.

What’s Really Being Done?

Behind the scenes, hospitals are improvising. Some are pooling resources. Others are turning to international suppliers, even if it means paying triple the price. Pharmacies are rationing. Patients are being told to wait. In some states, paramedics are being trained to administer alternative drugs because the standard ones are gone.

Meanwhile, 87% of physicians say they’ve had to change a patient’s treatment plan because of a drug shortage. And yet, only 12% even knew H.R.1160 existed. That’s not ignorance-it’s neglect. When Congress can’t even tell its own constituents about bills meant to save lives, it’s clear the system isn’t working.

There’s one bill that might actually help: S.872, the Stop Secret Spending Act. It doesn’t mention drugs or doctors. But it would force the Treasury Department to track spending more transparently. If lawmakers can see where every dollar goes, maybe they’ll notice that $45 million for the FDA’s shortage system is a tiny price to pay compared to the cost of emergency room backups, delayed surgeries, and preventable deaths.

What Happens Next?

If the shutdown doesn’t end by January 30, 2026, both bills die. They don’t get revived. They don’t get reintroduced. They vanish. The 119th Congress ends. The 120th doesn’t start until January 2027. That’s a full year without progress.

And in that year, more people will die. More families will be forced to choose between rent and medication. More nurses will burn out. More hospitals will close their doors to patients who need care.

The solutions exist. Better reporting. More funding. Clearer definitions. Workforce investment. But without political will, they’re just words on a page. The question isn’t whether Congress can fix this. It’s whether they’ll try before it’s too late.

9 Comments

Tola Adedipe

Let’s be real-this isn’t about policy, it’s about power. Companies don’t report shortages because they profit from scarcity. Fewer drugs = higher prices = bigger margins. The FDA’s backlog? That’s not incompetence, it’s corporate capture. S.2665 is a joke without penalties. You don’t just ask nicely when someone’s making billions off your kid’s insulin. They need to be fined daily until they comply. And yeah, I’m mad.

Niel Amstrong Stein

bro the shutdown is just… wild. like, imagine your doctor calling you saying ‘sorry, we can’t get your chemo because the feds are arguing about border wall funding.’ 😅 i get that politics is messy, but this? this is like letting your house burn down because you can’t agree on who gets the garden hose. the FDA portal showing drugs as ‘available’ when they’ve been gone for weeks? that’s not a glitch, that’s cruelty disguised as bureaucracy.

Joey Gianvincenzi

While I appreciate the emotional urgency of this piece, it is imperative to acknowledge that legislative efficacy cannot be measured solely by public sentiment. The absence of H.R.1160’s text precludes any substantive evaluation of its provisions. To assume its intent based on anecdotal healthcare workforce gaps is an analytical fallacy. Furthermore, the assertion that $45 million is a trivial sum ignores macroeconomic constraints and opportunity costs inherent in federal budgeting. We must ground discourse in data, not despair.

Marcus Jackson

Actually, the real issue is that 63% of shortages come from overseas manufacturing. That’s not Congress’s fault. That’s globalization. If you want to fix this, stop importing 80% of your active pharmaceutical ingredients from one country with shaky quality control. Build domestic capacity. Tax imports. Stop outsourcing everything and then cry when it breaks. The FDA can’t fix supply chains they don’t control. The bills are distractions.

Natasha Bhala

honestly i just want someone to fix this before my mom runs out of blood pressure meds again

Jesse Lord

the fact that we’re even having this conversation is wild. people are dying because a bill hasn’t been read. hospitals are scrambling. nurses are quitting. and congress is stuck on whether to fund a TV channel or a fence. i get that politics is broken but this feels personal. we all know someone who’s been affected. why does it take a crisis this big to make us care?

Catherine Wybourne

Oh honey, you think this is bad? Wait till you see the 2027 version where we’re rationing aspirin because the Chinese factory had a fire and Congress forgot to fund the backup plant. 😅 Meanwhile, someone’s tweeting about how ‘the system works’ while their neighbor’s kid goes without insulin. The real tragedy isn’t the shutdown-it’s that we’ve all stopped being shocked.

Amit Jain

you guys are overthinking this. the problem is WEAK LEADERSHIP. if america had real leaders, they’d just mandate domestic production. shut down all foreign drug imports until we build our own factories. no more ‘let’s study it for 5 years.’ no more ‘we need a task force.’ we need a war footing. this isn’t policy-it’s survival. if you’re not for forcing pharma to make drugs in america, you’re part of the problem.

Sarah B

stop blaming congress. the real issue is that liberals want to import drugs from China and Canada while defunding our own manufacturers. if we stopped outsourcing and started investing in American pharma instead of woke diversity programs, we wouldn’t have this problem. this isn’t a shortage-it’s a betrayal of American workers.