Muscle Tear Recovery Time Estimator

Understanding a muscle tear can feel overwhelming, especially when the injury strikes during a game or a workout. This guide breaks down everything you need to know about acute skeletal muscle tears - from what they are, how they happen, how doctors grade them, to the best ways to heal and get back in action.

What is an Acute Skeletal Muscle Tear?

Acute Skeletal Muscle Tear is a sudden disruption of muscle fibers caused by excessive force or rapid stretching. Unlike chronic strains that develop over time, an acute tear occurs instantly, often with a sharp pain, a popping sound, and immediate loss of strength in the affected limb.

How Do Muscle Tears Happen?

Most tears involve the Muscle Fiber, the basic contractile unit of a muscle. When a fiber is pulled beyond its capacity - think sprinting from a dead stop, lifting a weight that’s too heavy, or an unexpected change in direction - the fibers can stretch, partially tear (Grade I), or fully rupture (Grade III).

Key risk factors include inadequate warm‑up, fatigue, previous injuries, and muscle imbalances. Athletes in high‑speed sports such as soccer, rugby, and track are especially vulnerable because the forces involved can exceed the muscle’s tensile strength in milliseconds.

Grading Muscle Tears: From Mild to Severe

Doctors use a three‑tier system to describe the extent of damage:

| Grade | Fiber Disruption | Typical Pain Level | Functional Loss | Recovery Time |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Grade I (Minor) | Microscopic tearing, Muscle Fiber strain | Low to moderate, often described as a dull ache | Minimal, can usually continue activity with caution | 1‑3 weeks |

| Grade II (Partial) | Visible fiber discontinuity, Strain Grade intermediate | Moderate to severe, sharp pain at injury moment | Significant loss of strength, limited range of motion | 4‑8 weeks |

| Grade III (Complete) | Full‑thickness rupture, often with a palpable gap | Severe, sudden loss of function | Complete inability to use the muscle | 3‑6 months, sometimes surgical intervention |

Knowing the grade guides treatment decisions, which we’ll explore next.

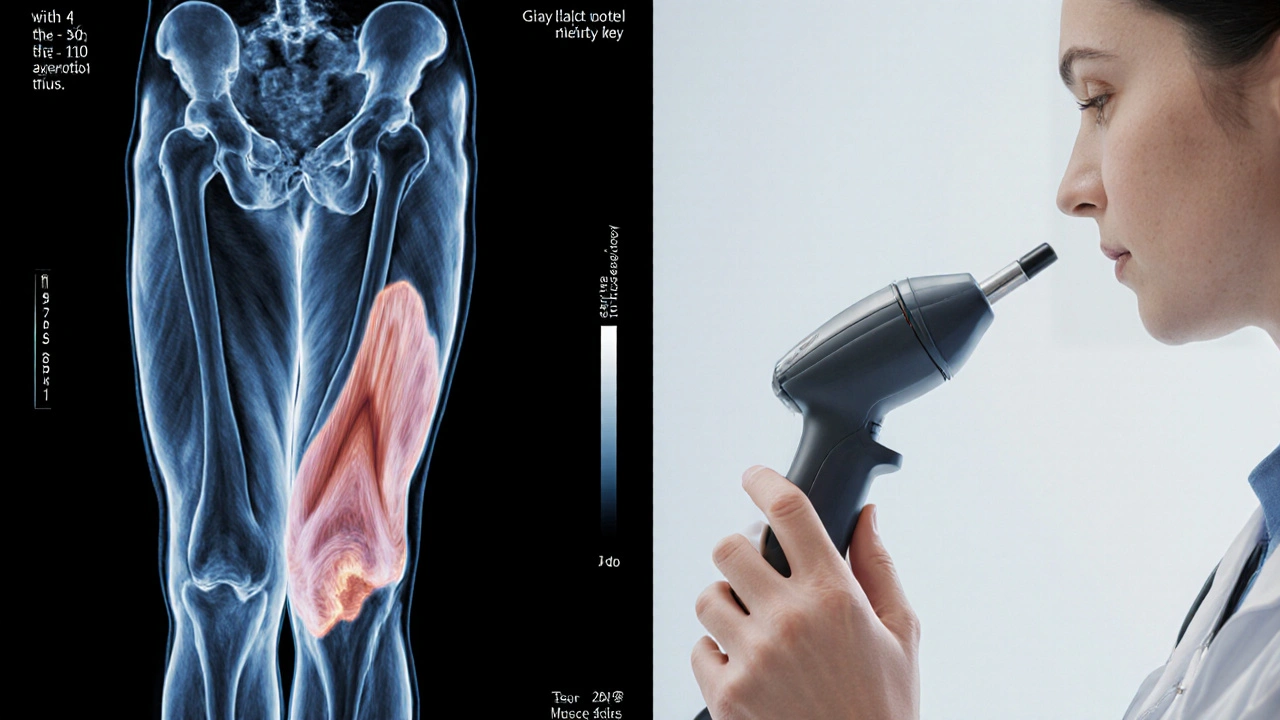

Diagnosing an Acute Muscle Tear

Initial diagnosis relies on a physical exam - the clinician feels for tenderness, swelling, and gaps in the muscle. However, imaging gives a clearer picture. The gold‑standard tool is Magnetic Resonance Imaging (MRI), which visualises the exact location and size of the tear, helping differentiate a Grade II from a Grade III injury.

Ultrasound is another option, especially for bedside assessment, but its accuracy depends heavily on the operator’s skill.

Immediate Management: The RICE Protocol

The first 48‑72 hours are critical. Most clinicians recommend the RICE Protocol - Rest, Ice, Compression, and Elevation.

- Rest: Avoid loading the injured muscle; use crutches or a sling if needed.

- Ice: Apply a cold pack for 15-20 minutes, three times daily, to reduce swelling and pain.

- Compression: Elastic bandages limit fluid buildup, but keep pressure moderate to prevent circulatory issues.

- Elevation: Raise the limb above heart level when possible.

While RICE is essential, it’s not a cure. After the acute swelling subsides, you’ll transition into active rehabilitation.

Choosing Between Conservative and Surgical Treatment

Most Grade I and many Grade II tears heal well with non‑surgical care, which includes structured Physical Therapy. A therapist will guide you through gentle stretching, progressive strengthening, and neuromuscular re‑education.

Grade III tears, or Grade II tears that don’t improve after 2-3 weeks of therapy, often require Surgical Repair. Surgeons re‑approximate the torn ends using sutures or anchors. Post‑op protocols typically involve a brief immobilisation phase (2‑3 weeks) followed by a gradual rehab program.

Decision‑making should involve a Sports Medicine Physician who can weigh factors like the athlete’s level, the muscle involved, and the timeline for return to competition.

Rehabilitation: Getting Back to Full Function

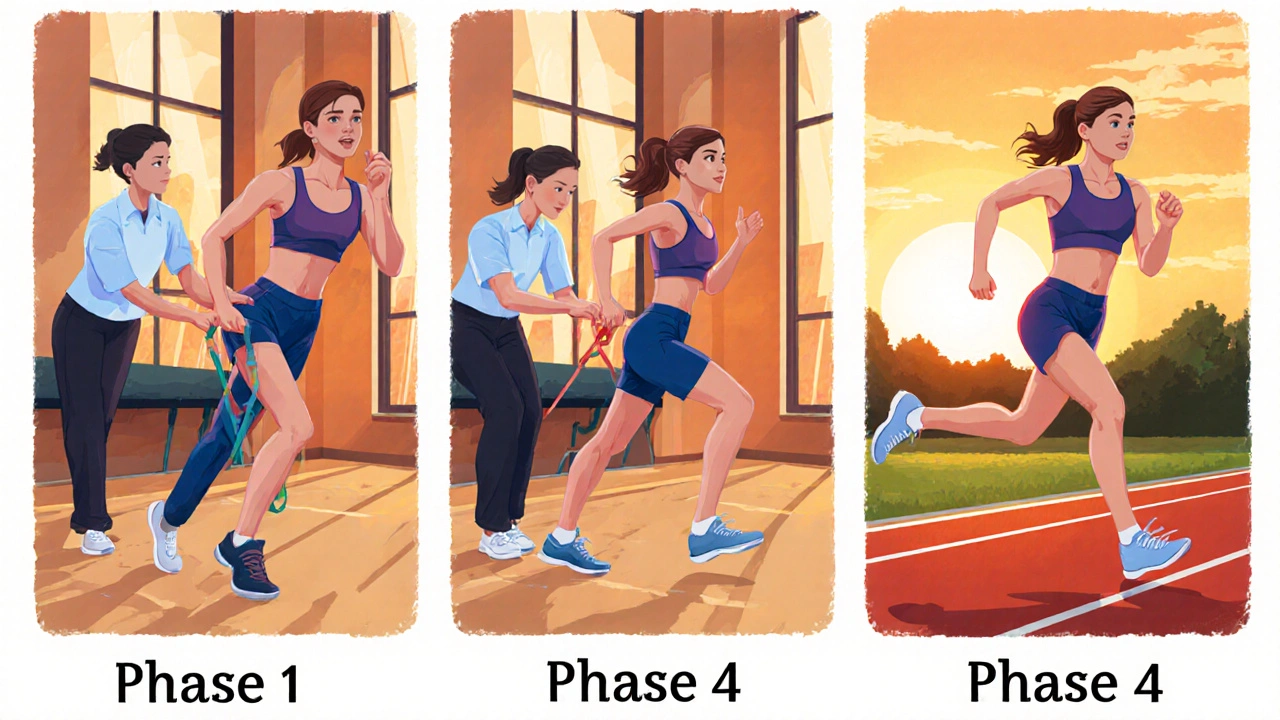

Rehab is a staged process:

- Phase 1 - Protection & Pain Control (Weeks 0‑2): Gentle range‑of‑motion exercises, isometric contractions, and continued RICE.

- Phase 2 - Early Strengthening (Weeks 2‑6): Light resistance bands, closed‑chain movements, and low‑impact cardio (e.g., stationary bike).

- Phase 3 - Advanced Strength & Power (Weeks 6‑12): Progressive loading, plyometrics, and sport‑specific drills.

- Phase 4 - Return to Sport (Weeks 12+): Full‑speed running, cutting maneuvers, and functional testing before clearance.

Throughout, Rehabilitation specialists monitor muscle balance, flexibility, and neuromuscular control to minimize re‑injury risk.

Prevention: Keeping Muscles Strong and Flexible

Prevention isn’t magic; it’s about consistent habits:

- Warm‑up dynamically - leg swings, high knees, and light jogging raise muscle temperature.

- Strengthen both agonist and antagonist muscles - hamstring‑quad balance is a classic example.

- Incorporate eccentric training - slow lowering phases improve tendon resilience.

- Maintain flexibility - static stretching after workouts helps preserve optimal length‑tension relationships.

- Address fatigue - schedule rest days and monitor workload to avoid overuse.

When you combine these practices with regular check‑ins from a qualified therapist, the odds of suffering an acute tear drop dramatically.

Frequently Asked Questions

How can I tell if I have a Grade II muscle tear?

A Grade II tear typically causes sharp pain at the moment of injury, noticeable swelling, and a marked loss of strength. You may feel a “tugging” sensation when trying to move the muscle. An MRI will confirm the diagnosis by showing a partial fiber disruption.

Is surgery always required for a complete (Grade III) tear?

Not always, but it’s often recommended for athletes who need a rapid and reliable return to high‑level performance. Non‑surgical rehab can work for low‑demand individuals, though recovery may be slower and functional deficits more likely.

Can I use heat instead of ice during the first few days?

Heat raises blood flow and can increase swelling, so ice is preferred in the acute phase (first 48‑72 hours). After swelling subsides, alternating heat and ice may help with muscle relaxation and pain relief.

How long before I can run after a Grade II tear?

Most clinicians clear light jogging around weeks 4‑5, provided pain‑free range of motion and strength are at least 80% of the uninjured side. Full sprinting usually resumes after weeks 6‑8.

What role does nutrition play in healing a muscle tear?

Protein supplies the amino acids needed for muscle repair, while vitamin C and zinc support collagen synthesis. A balanced diet with 1.6-2.2g protein per kilogram of body weight daily speeds recovery.

11 Comments

Kelly Diglio

Thank you for putting together such a thorough overview of muscle tears. The breakdown of the grading system is especially helpful for athletes who need to understand the severity of their injury. I appreciate the clear explanation of the RICE protocol and how it transitions into progressive rehabilitation phases. It is also good to see the emphasis on nutrition and balanced protein intake for optimal healing. Overall, this guide serves as a solid reference for both patients and clinicians alike.

Carmelita Smith

Great summary, very handy! 😊

Liam Davis

The pathophysiology of an acute skeletal muscle tear involves a rapid overload of tensile forces that exceed the sarcomere's elastic limit.

When this occurs, the contractile proteins are mechanically disrupted, leading to microscopic or macroscopic fiber separation.

Clinically, the sudden onset of sharp pain, a popping sensation, and immediate functional loss are hallmark signs.

Imaging modalities such as MRI provide high-resolution visualization of the injury, allowing precise grading between I, II, and III.

Ultrasound, while operator‑dependent, offers a bedside alternative that can detect fluid collections and tendon retraction.

The initial management strategy, RICE, remains the cornerstone of care during the first 48–72 hours.

Rest prevents additional mechanical loading, whereas ice mitigates inflammatory edema through vasoconstriction.

Compression limits interstitial fluid accumulation, and elevation assists venous return, collectively reducing swelling.

Following the acute phase, a structured rehabilitation program should commence, emphasizing controlled range‑of‑motion exercises.

Isometric contractions in early stages help maintain neuromuscular activation without imposing excessive strain.

Progressively, resistance training with bands and closed‑chain movements rebuilds muscular strength and joint stability.

For Grade III tears, surgical intervention is often indicated to restore the continuity of the musculotendinous unit.

Post‑operative protocols typically involve an immobilization period of two to three weeks, after which gradual loading is reintroduced.

Nutrition plays a non‑negligible role; adequate protein (1.6–2.2 g·kg⁻¹·day⁻¹) supplies the amino acids necessary for myofiber repair.

Micronutrients such as vitamin C and zinc facilitate collagen synthesis, further supporting tissue remodeling.

By adhering to these evidence‑based guidelines, athletes can expect a safe return to sport while minimizing the risk of re‑injury. 😊

Arlene January

Whoa, that table really nails how the grades differ! I love the part about dynamic warm‑ups – they’re a game‑changer. If you’re dealing with a Grade II, don’t skip the early strengthening; it makes a huge difference. Keep pushing, and you’ll be back on the field before you know it.

Kaitlyn Duran

Do you think adding some plyometric drills in Phase 3 speeds up the return for runners? I’ve read that it can improve power without risking re‑tear if done cautiously.

Terri DeLuca-MacMahon

Absolutely! 🎉 Introducing low‑impact hops and box jumps after you’ve regained full range‑of‑motion can boost neuromuscular coordination!!! Just keep the volume low and focus on landing mechanics!!! 🏃♀️💪

gary kennemer

One point worth adding is the role of eccentric training during Phase 2; it specifically targets the length‑tension relationship that’s often compromised after a tear. Additionally, monitoring load progression with a perceived exertion scale can prevent over‑training. Make sure to reassess gait and movement patterns regularly to catch compensations early. Finally, integrating core stability work helps distribute forces more evenly across the kinetic chain.

Payton Haynes

The “gold‑standard” MRI hype is just a way for big hospitals to charge extra fees. A good ultrasound can give you the same info if you know what to look for.

Earlene Kalman

That’s a ridiculous claim; imaging is essential for proper diagnosis.

Brian Skehan

Even if you think it’s essential, remember that many studies are funded by imaging companies, so the data can be biased. It’s always wise to question who benefits from the recommended tests.

Andrew J. Zak

Interesting points on eccentric work and load monitoring. It’s also good to consider cultural differences in rehab expectations, as some athletes prefer more holistic approaches.